Lighthouse Chapel begs court for more time to file defence

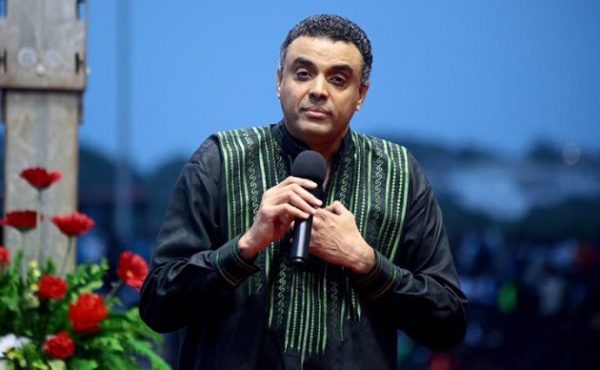

Rodney Heward-Mills stood up in court, tall. His Dag-hued skin bore the unmistakable genetic print of a relative of Bishop Dag Heward-Mills, whose church, Lighthouse Chapel International, has been dragged to court over the non-payment of SSNIT, abuse, and exploitation.

His English revealed a British accent and it was fast and furious; fast enough to give a journalist cocooned within the four borders of this country a torrid time at quickly decoding his speech.

And his tone was serious, almost flirting with furious, enough to set the courtroom on the edges.

This was the first hearing of a case brought against the charismatic church by six former employees—four pastors and two bishops—who had served for a cumulative 70 years but whose SSNIT contributions were not paid for some 42 years and some odd months.

They had filed their cases individually on April 14, and their writs were served on Lighthouse Chapel International on April 23, which meant that the church was to file responses within 14-days.

But more than one month had elapsed and the church had failed to file even one response within the period stipulated by the rules of court.

And so, Rodney Heward-Mills, counsel for the church, stood up in court to explain the failure and to plead for more time to file their defence statements.

He said the church had been “inundated” by the six suits all filed on the same day. And so having to respond to each of them with the 14-day period presented a “unique situation” which made the deadline hard to meet.

“To cut a long story short, we ask that you give us more time,” Heward-Mills summarised.

But, to Kofi Bentil, the lawyer for all six, this excuse wouldn’t cut it.

“We don’t find the argument tenable,” Mr. Bentil, on his feet, shot back, explaining that the six different cases had a similar thread of abuse and exploitation which should make it fairly simple for the defendant to respond.

He said any law firm should not find it extraordinary a feat to file six responses to six suits. That is the job of law firms.

The judge, Justice Frank Aboagye Rockson, applied some brakes to the early signs of dramatic exchanges. As a judge, he was all too familiar with courtroom maneuverings and he knew that all the plaintiff was asking for was for the court to award cost against the defendant’s explained failure to file responses.

Bentil wanted GH₵2,000 cost and some short extra time for the defendant to file responses. Rodney Heward Mills got feisty, threw his arms, gesticulating some deal of exasperation, complaining that the sum was too much, and asked the judge to waive the costs completely.

He said as a show of good faith, he had filed a 64-page response to the suit by Larry Odonkor only yesterday. “We are just asking for some time,” he begged the court.

The judge studied Rodney Heward-Mills and asked gently, how much time the defendant would need.

“Can you give us 21 days?” his request drew a sensational dissatisfaction from Kofi Bentil’s face that suggested 21 extra days after the failure to meet the 14-day deadline was just asking for too much. The judge gave 14 days and awarded GH₵1,000 as a cost against Lighthouse Chapel International.

Because the six former employees had filed their cases separately, each case was called separately. And after three of their cases were heard with the same argument of the defendant asking for more time and the plaintiff hoping for more cost, the trial settled into some monotonous drama.

“My Lord, the same argument,” Rodney Heward-Mills would say, to which Kofi Bentil would reply, “My Lord, the same argument.”

For the lawyers who did not see eye to eye, they now, at least, eyed one argument.

Eyeing what was happening, Justice Frank Aboagye Rockson joined in the monotony and gave similar rulings, awarding GH₵1,000 as cost in all the cases except Larry Odonkor’s and extending the deadline for filing responses to 14 days in all the cases except Larry Odonkor’s.

The exception was because the counsel for LCI had indicated that he had filed a response to Larry Odonkor and so the judge award GHc500 as a cost for the defendant’s inability to file within the stipulated time. The court also gave the plaintiff, Larry Odonkor, 10 days to respond.

The judge, after hearing all six cases, commented that the cases were all similar. “Look at it and see if it can be consolidated. There is room for settlement,” he said, drawing attention to a quiet resolution than a bloody court battle, opulent in drama, jaw-dropping in its revelations.

“You should not shy away from it,” he encouraged the counsel for the defendant and for the plaintiffs who were tasked to help people find Christ but who now cannot find their SSNIT contributions.

Larry Odonkor and his five other colleagues sat through the proceedings at the Labour Court 1 in the Law Court Complex reverently like newcomers to the world of litigation. The court they have been familiar with is the one they have preached for years, that the world should expect on Judgment Day.

That court will have a great potentate, the Judge sitting immaculately in invisible light, ready to deliver a hair-dryer treatment for proud sinners. This court in Accra just had air-conditioning and a pleasant judge wearing a white wig, though not as white as Apostle John’s description of Jesus’ hair.

But human judges are also empowered by God to deliver justice, and so the six ministers of the gospel believe that coming before His Lordship is a just route after all attempts to dialogue with the church had failed.

One of the plaintiffs, Rev. Edward Laryea, sat in court with the woman who had sat with him through their “ordeal” as missionaries of Lighthouse Chapel International from 2005 to 2017.

Her name is Ariel Laryea. And she is his wife who, like many others, resigned from her job as a laboratory technician at Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital to do full-time ministry along with her husband.

Her husband is full of adoration for her sacrifices. “My wife has suffered a lot oo. She has suffered,” he once told The Fourth Estate, explaining she suffered two miscarriages plying womb-dislocating roads in the Eastern region where they preached the gospel and opened several branches of the church.

The church did not foot a single health bill of his wife or take adequate care of them, they have alleged.

But sitting in court, Ariel Laryea had covered her many emotional bruises in neat physical apparels of beauty. The pain was there. But the smile was also there, sitting side by side in the life of a woman who also gave her all for the Lord’s work along with her husband but who claimed they have received the shock of their lives at Lighthouse Chapel International.