Beyond the Stats: Evaluating Galamsey’s Effect

Ghana’s economy, water resources, and land are being severely damaged by galamsey, or illicit mining. The situation on the ground is still grave even as the #SayNoToGalamsey movement gathers traction on social media and organised unions, as well as the clergy, start to express their objections.

Clean water is getting harder to come by, cocoa crops are getting smaller, and smugglers are taking gold from legitimate mines. There is no denying the harm, and the stakes are higher than ever.

Cocoa’s Golden Years Fading

In 2020, the Ghana Cocoa Board (Cocobod) reported that 20,000 hectares of cocoa farms were lost to galamsey. That number has almost certainly increased since then. Faced with climate change and the spread of the swollen shoot virus, cocoa production has been steadily declining.

This has trapped farmers in a vicious cycle: as yields and incomes drop, they are more likely to sell their land to illegal miners. The survival of Ghana’s cocoa sector is now under serious threat.

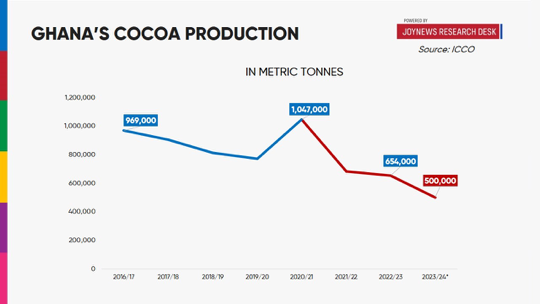

Production figures tell the story. By 2027, Ecuador is expected to surpass Ghana in cocoa output, according to the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO). Ghana, which produced 960,000 metric tonnes of cocoa in 2016, briefly peaked at 1 million tonnes in 2021. But production has since plummeted, reaching only 654,000 tonnes last year. This year, it is expected to fall below 500,000 tonnes.

From Sweet Exports to Sinking Revenue

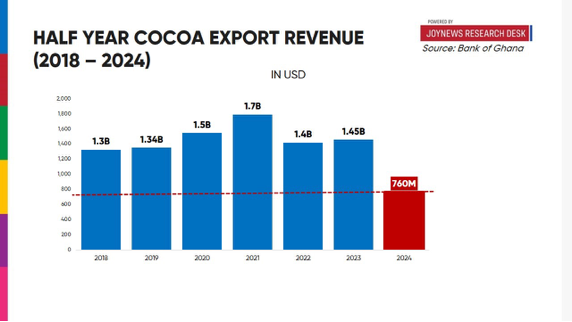

The effects of this decline go far beyond the farms. Cocoa is a major economic driver, and lower production is hurting Cocobod’s ability to secure loans, which have been essential for stabilizing the cedi. Earlier this year, Cocobod couldn’t fully use its syndicated loan due to insufficient cocoa collateral.

As cocoa export revenues drop—this year’s are about half of what they were during the same period last year—the economic strain deepens. Data from the Bank of Ghana summary data shows that cocoa export revenues for the first two quarters of this year hit their lowest point since 2018, marking a $693 million decline compared to the same period last year.

Illegal mining isn’t just affecting cocoa; it’s also damaging the gold sector. The Economic and Organized Crime Office (EOCO) estimated that from 2019 to 2021, Ghana lost $1.1 billion from unreported gold exports, much of it smuggled out of the country by illegal miners. This is a stark reminder of the broader economic damage galamsey is causing.

A Turbulent Turn in the Water

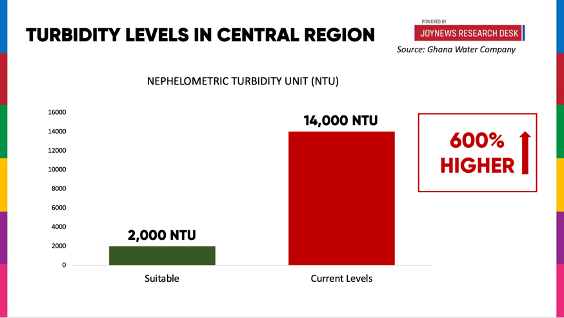

The impact on water supplies is equally alarming. According to the Ghana Water Company, for water to be suitable for purification, turbidity levels should be around 2,000 Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU), but pollution from illegal mining has pushed levels as high as 14,000 NTU in some areas—an astonishing 600% increase.

The Ghana Water Company reports that 60% of its reservoirs in the Central Region are clogged with silt, leaving many of its plants operating at just 25% capacity. Water production across the country has also dropped to 40%, down from 70% in 2022, and the once-unthinkable prospect of Ghana needing to import water is becoming a real possibility.

The environmental damage is devastating as well. According to Ghana Forest Watch, the country has lost 24% of its tree cover—equivalent to 1.46 million hectares—over the last two decades. The regions most affected by deforestation are those where galamsey is most rampant: Western, Ashanti, Eastern, Central, and Brong Ahafo. These are also the areas facing the worst water shortages.

Ghana’s fight against galamsey is not just about stopping illegal mining—it’s about protecting its natural resources, agricultural productivity, and economic future.

In 2021, the government resorted to burning excavators found at illegal mining sites to deter miners. But unless real economic alternatives are provided to those involved, such drastic measures will do little to stop the problem.