‘I’m a bad person, and I need to die,’ – Sex predator confesses as police arrest him

In the following comprehensive report, Manasseh Azure Awuni of The Fourth Estate recounts the emotional moments of Jonathan Ohene Nkunim’s arrest and his confession to Manasseh and the Police. Read the report before:

When Jonathan Ohene Nkunim beckoned his wife for a parting hug, it was like a scene from a romantic movie.

She hesitated, as if unsure whether to give in or pull away. Then she obliged.

He moved towards her; his arms outstretched. Hers were folded across her chest. And she leaned forward for a hug without maintaining eye contact with the tall man who held her tenderly and looked at her with affection.

It was a slow-moving act, filled with emotions.

Mr. Nkunim whispered words of encouragement. They appeared not to affect her mood. She was distraught. And justifiably so.

It was 7:30 a.m., and Mrs Nkunim, who was nursing a three-month-old baby, was the subject of the prying eyes of half a dozen uninvited guests. They had intruded her home and ruined the sanctity of her early morning privacy.

The guests, who had not given her a clue about their visit, said little. But their presence provided enough clues that her eight-year-old marriage might never be the same.

Even if she did not expect the unsolicited morning visit, she had, in the past 24 hours, anticipated disruption to her life and those of every member of her family.

The previous day, she had seen the trailer of an investigative documentary that was yet to be aired. The documentary was titled “The Unlicensed Sex Predator”. For the right or wrong reason, someone had forwarded the trailer to her.

The trailer quoted the villain in the investigative piece as boldly proclaiming, “If it were to be true, I should be in jail by now.”

The man who made that bold pronouncement was her husband, Jonathan Ohene Nkunim, the man who had taken a vow to be faithful to her.

He was accused of sexually abusing women who visited his health facility, Nature’s Hand Therapeutic Centre, in Gbawe. When the investigative journalist first asked him, he denied the allegation and dared his accusers to prove it.

“I wanted to confess to you, but I didn’t know whether I could trust you or not,” he would later tell the journalist. The journalist was among the six men who visited his home that morning. The others were police officers from the Police Intelligence Directorate (PID).

Mrs Nkunim was not only worried that allegations of that gravity were levelled against her husband. She and her husband knew the allegations were true because he said he had confessed to her.

Mr Nkunim had told the visitors that his wife was his main worry in the unfolding scandal. The nursing mother was going to be hit hard by the impending doom. His shame would maim the collective fame of the gospel-singing couple.

So, Mrs Nkunim’s expressions, like someone who was too shocked and sad to cry, were understandable. Her marriage was at the tipping point of possible ruin. And that was because her husband had ruined other marriages and relationships.

His victims included a couple who had gone to Nature’s Hand Therapeutic Centre in 2018 to seek his help to be able to conceive. He ended up sleeping with the woman. She felt guilty about the affair and confessed to her husband. And that was how the seven-year-old marriage ended.

A young woman was on the verge of suicide because the heart-wrenching pain from her spinal cord convinced her that ending her life was a better option. Someone offered her a lifeline, Jonathan Ohene Nkunim’s hotline.

Ohene Nkunim raped her the first day she entered the facility in pain and lay on the massage bed.

He left incriminating evidence in his WhatsApp conversation with her after the ordeal. He admitted he did not seek her permission before having sex with her. Mr Nkunim claimed the procedure he wanted to perform required sexual arousal. He said he should have “sensitised” her before proceeding. Mr Nkunim then apologised profusely. But he did not stop.

The next time she visited, he had sex with her. It happened until she left for another facility to continue the treatment.

These and other victims had suffered silently because of the shame associated with their ordeal–sex. They said they feared to speak up in a system that blamed the victims rather than the perpetrator. Despite their fears, they eventually found their voices and opened up to a journalist they felt they could trust.

Jonathan Ohene Nkunim, had been fearing for a day like this, but he often hoped it would never come. Three months ago, when the investigative journalist from The Fourth Estate visited him, he denied every allegation. That visit and a subsequent enquiry from the health regulatory body by the journalist resulted in a temporary closure of his facility. But he found a way out and got the place up and running again.

In his mind, he had scaled a dangerous hurdle and life was getting back to how it used to be. But the trailer of the documentary unsettled him

That morning, Jonathan Ohene Nkunim told the police and journalists that he had summoned the courage to confess to his wife about his bad deeds-–his uncontrollable sexual escapades. His wife had understood him, he claimed and was helping him to reform.

“And now, this!” he spoke with tears in his eyes about the investigative documentary.

He would later tell the police during interrogation that he had lost count of the number of women he had sexually abused at his facility.

It is not clear whether he made the confession to his wife before or after the trailer was published, but there was one thing he may not have told his wife. It was the reason the couple had the visitors in their house.

When the trailer was published, he called and texted the journalist who produced the documentary to declare his intentions.

When the journalist could not answer his first set of calls, he left a text message: “I have poison in my hands right now…and I just need someone to talk to…I am sorry.”

He immediately followed that with another text message: “I am a bad person and I need to die.”

When the journalist spoke with him later, Jonathan Ohene Nkunim emphasised his readiness to end his life if the investigative documentary aired. He said he could not bear it.

He also mentioned the possibility of committing suicide to a former minister of state he had called to intervene and try to stop the documentary from airing.

And at 2:00 a.m. on Wednesday, a popular radio presenter, who spoke to the investigative journalist on the phone on behalf of Nkunim, repeated the same threat from Ohene Nkunim.

By 6:30 a.m., the plain cloth police personnel from the PID had picked him up behind the Law Faculty of the University of Ghana, about 20 kilometres from his home.

From the University of Ghana, the police wanted to visit his facility at Gbawe CP, but he had left the key to his office at home. So, he had to be taken home to pick it.

Before the police entered his house, however, he had a plea. He didn’t want to enter his apartment in handcuffs. His wife and children could not bear to see him shackled. He could not bear the inquisitive stare of curious neighbours. He did not want to cause a stir.

The police did not want to take chances. Their superiors would not forgive them if they went back to report that they had picked up the crime suspect who was threatening to commit suicide but could not restrain him from carrying out his threat when they got to his residence to pick a key.

Apart from one curious neighbour, a man in his sixties, sitting outside his gate with a radio set, the presence of the uniformed police in two unmarked vehicles and two journalists from The Fourth Estate in another vehicle did not create a scene.

The Director-General in charge of Operations at the Ghana Police Service, DCOP Mohammed Fuseini Suraji;and the Director-General in charge of the Police Intelligence Directorate, ACP Faustina Koduah Andoh-Kwofie; had each called and spoken with the leader of the team during the operation. They both emphasised the need for the suspect to be treated with dignity.

It appeared, for the first time in living memory, the Ghana Police Service, under the leadership of IGP Dr George Akufo-Dampare was living its motto: Service with Integrity.

Less than 12 hours before that operation, the police had interdicted four of its men for assaulting suspects in the Northern Region and had commenced disciplinary actions against them. So it wasn’t strange that the senior police officers emphasised the rights and dignity of Ohene Nkunim, especially when journalists were involved.

Outside the Nkunim’s apartment, the police weighed the instruction of their superiors against the safety of the suspect as well as the emotions of his family members. They removed the handcuffs but walked close to him. In the house, they assumed a friendly posture.

Before they entered the house, Mr. Nkunim asked for one more favour. His daughter was leaving for school and should not see him in that state. The police obliged and went in after the driver drove out of the gated apartment with two innocent children in the back seat.

When Jonathan Ohene Nkunim’s mother-in-law asked about their mission, the leader said he was their friend and they were going with him to resolve an issue that needed his presence. Perhaps he did not want the frail old woman to wail.

Jonathan’s last words in his house that morning were to his mother-in-law. He told her to take care of his wife while he was away, unsure how long he would be away.

In the car with the police and at Nature’s Hand Therapeutic Centre, Ohene Nkunim made more confessions. He said he had been helpless with his sexual desires and had often felt guilty after sleeping with his patients at the facility.

He had sought help but failed.

“Is it spiritual?” the investigative journalist asked. Jonathan had projected himself on social media as a very spiritual Christian.

“I won’t say it’s spiritual,” he replied and blamed it on the neuromuscular diagnosis method.

“It’s random. It’s not like every woman I see,” he told the investigative reporter that he did not sleep with some of the women who visited his facility.

“It’s guilt and regret. It’s guilt and regret, and I’ve worked on it.” he broke down in tears and asked for a second chance in order to reform.

That second chance is likely to be decided by the court. The police are going to press charges. And some of his victims quoted in the investigative report will testify in court.

The Fourth Estate can report that Nkunim has been cautioned on the charge of rape. The police have taken witness statements, including one from his victim. Apart from the sex offences, the police are also looking at breaches of health regulation laws.

At his facility that Wednesday morning, two vehicles were already waiting for him when he arrived with the police.

“I have got some issues to sort out, so there will not be any treatment today,” he told them in a way that did not suggest he was in trouble. The police still did not want to create a scene, so they allowed him to interact freely with his clients.

As the clients were leaving, he led the police to open the facility. Inside the facility, there were about 700 patients’ folders. He said about 200 of them were active patients. The rest had been treated and discharged.

“I have told my workers not to come to work today,” he said when asked when business for that day would start.

“When I was going out today, I knew I would not come back,” he added.

When he left for the University of Ghana that early morning, he intended to meet the investigative journalist and find out how he could stop the documentary from airing. “I will do whatever it takes,” he had told the journalist on the phone.

The navy-blue Bolt driver that drove him from home to the university bolted from the Law Faculty car park when he suspected that the two vehicles parked at the other side might be after him.

The journalist and his cameraman had been accosted by the security guards of the law school, one of whom was agitated that the faculty was being filmed without his consent. A heated argument ensued. The two security personnel, a police officer and the two journalists from The Fourth Estatewith the camera in hand were enough to alarm any suspect.

Ohene Nkunim left before anyone noticed his presence. But the investigative journalist noticed that the vehicle that had parked near his vehicle pulled away suddenly without anyone alighting from it.

“Where have you reached, please?” he asked Jonathan Ohene Nkunim on the phone.

“I’ve entered and I’m going round to locate where you are,” Nkunim said.

“Did you come in our car or in an Uber?”

“I came in an Uber?”

“What’s the colour of the Uber?”

“It’s white,” Nkunim said after some hesitation.

At this stage, the investigative journalist was convinced Nkunim was the one in the blue vehicle that left the car park unceremoniously.

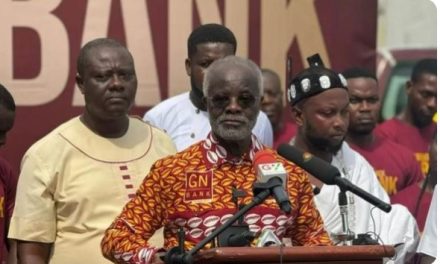

He alerted the police, and they traced it to the back of the Law Faculty, where Jonathan Ohene Nkunim was dressed in a multicoloured African print with black trousers and a pair of black shoes.

He surrendered his freedom to the law enforcement officers. And would fight for that freedom in the days that would follow.

He appeared to have accepted his fate. His last plea before he was taken to the police headquarters was that the documentary should be shelved for the sake of his family.

“Let’s see what happens,” the journalist said.